GE Aerospace's Earnings Beat Is Not the Real Story. This Is.

You could almost hear the collective sigh of relief from trading desks on Tuesday morning. When GE Aerospace dropped its third-quarter earnings, the numbers didn’t just meet expectations; they dismantled them. Adjusted revenue soared 26% to $11.3 billion. Earnings per share landed at $1.66, a clean beat over the $1.47 Wall Street consensus. The market did its part, dutifully pushing the stock up over 2.5% in response. GE Aerospace Stock Notches Record High On Beat-And-Raise Report.

On the surface, this is a simple story: a blue-chip industrial titan is firing on all cylinders. The aviation industry is booming, and GE is reaping the rewards. CEO Larry Culp’s victory lap quote about an "exceptional quarter" with "44% EPS growth" certainly reinforces that narrative. But I’ve learned that the easy narrative is rarely the complete one. The market’s reaction, while positive, feels focused on the topline. My analysis suggests the far more compelling, and frankly more important, story is buried a little deeper in the financial statements—in the operational DNA of this newly streamlined company.

The headline numbers are just the exhaust fumes. The real action is happening inside the engine.

Deconstructing the Growth Engine

Let’s be precise. The primary driver of this quarter’s success was the commercial engines and services business. Orders were up 32%, and revenue grew by about 30%—to be more exact, 28%. The company even felt confident enough to raise its full-year revenue growth guidance for this segment from the "high teens" to the "mid-20s range." This is the engine of the entire enterprise, and it’s running hot.

But this is the part of the report that I find demands a closer look. An increase in orders and revenue is positive, but it lacks context. Is this growth coming from a temporary, post-pandemic sugar high as airlines rush to service their fleets and expand capacity? Or does it represent a fundamental, sustainable capture of market share? The press release doesn’t offer a clear distinction between high-margin services (the lifeblood of engine manufacturers) and lower-margin new engine sales (the razor blades sold to generate future service revenue). This ambiguity matters. A dollar of revenue from a LEAP engine service contract is worth far more to the bottom line over its lifetime than a dollar from selling the engine itself.

This isn’t just an academic distinction. It’s the core question of GE’s long-term profitability. We see the 32% order growth, but what is the quality of that backlog? How does the margin profile of these new orders compare to the existing service agreements? Without that data, we’re essentially looking at a car’s speedometer without knowing how much fuel is in the tank. The speed is impressive, but for how long can it be maintained?

The Real Story: A Masterclass in Conversion

This brings me to what I believe is the real signal in Tuesday’s report: financial and operational discipline. Larry Culp highlighted a staggering metric that most of the headlines seemed to gloss over: "more than 130% free cash flow conversion." This isn't just corporate jargon; it's the numerical proof of a profound transformation. Free cash flow (FCF) conversion measures how much of a company's net income is converted into actual cash. A rate of 100% is considered healthy. A rate of 130% is an outlier.

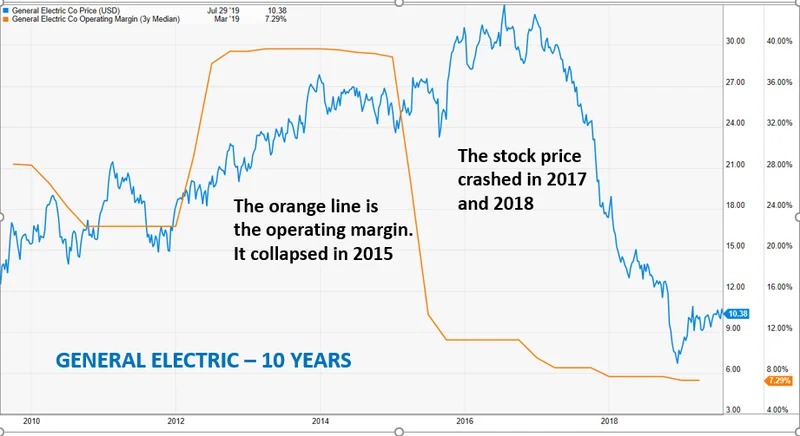

Think of the old, sprawling General Electric conglomerate as a leaky, inefficient engine. It burned a tremendous amount of fuel (capital) but produced disappointing thrust (shareholder returns) and an enormous amount of waste heat (bureaucracy, bad acquisitions, debt). The new GE Aerospace is the opposite. It’s a finely-tuned machine designed for one purpose: converting profit into cash with ruthless efficiency. That 130% figure means for every dollar of accounting profit GE earned, it generated $1.30 in cold, hard cash. This is achieved through disciplined management of working capital, inventory, and receivables—the boring, unglamorous work that separates truly great operators from the merely good.

This is the Culp effect, quantified. It’s the result of stripping the company down to its studs and rebuilding it with a singular focus. The raised full-year EPS forecast (now $6.00-$6.20) is a direct consequence of this operational rigor. The market reacted to the revenue beat, but the institutional money—the money that matters—is looking at this cash conversion and seeing a company that has fundamentally changed how it operates. The question, of course, is one of sustainability. Is this level of conversion a one-time benefit from post-spin-off clean-up, or is it the new baseline for the company?

A Textbook Execution

Let’s be clear: this was an objectively strong quarter. The market’s positive reaction is entirely justified. But to see this merely as a story of a booming aviation market is to miss the point entirely. The real story isn't that GE is selling more engines; it's that the company has finally learned how to run its business with the same precision as the turbines it manufactures. The revenue growth is the tailwind, but the operational efficiency is the engine. The former is cyclical and subject to market whims. The latter is a durable, structural advantage that will determine the company's trajectory for the next decade. The market may have cheered the speed, but I’m focused on the engineering.